Pricing policies constitute the general framework within which pricing decisions should be made in order to achieve the pricing objectives. They provide guidelines within which pricing strategy is formulated and implemented.

The following statements will clarify the meaning of pricing policy:

(i) Pricing should aim at maximising profits for the entire product line.

(ii) Prices should be set to promote the long-term welfare of the enterprise, e.g., to discourage competition in the market.

(iii) A predetermined and systematic method of pricing new products should be provided.

(iv) Prices should be adopted and individualised to fit the diverse competitive situations encountered by different products.

A systematic approach to pricing the products of a firm requires that decision of individual pricing situations be generalised and codified into policies covering all the principal pricing policies. Pricing policies should be tailored to meet the various competitive situations.

This implies that a firm can follow different pricing policies with regard to different markets or different customers. For instance, full cost pricing may be followed to sell the products to a big buyer like Government, particularly when the plant capacity is lying idle.

We can classify various pricing policies into the following categories:

(i) Demand-oriented pricing.

(ii) Cost-oriented pricing.

(iii) Competition-oriented or market driven pricing.

(iv) Value-based pricing.

1. Demand-Oriented Pricing:

The law of demand and supply states that “The quantity demanded goes up as the price goes down. And as the price goes up, quantity demanded goes down”. That is, there is an inverse relationship between price and quantity demand. As long as buyer’s need, ability (purchasing power), willingness and authority to buy remain stable, and as long as environmental situations remain constant, this fundamental inverse relationship will continue.

The basic price level is very much affected by the relationship of supply and demand. A shortage means that prices rise, while a surplus means that price decline. The effects of short supply are most apparent in the case of agricultural products and other raw materials. An inadequate supply of consumer goods-food grains, oil, sugar, tyres, etc. can push up the price of such goods. On the other hand, if the supply is large in relation to demand, its price tends to decline.

The demand may be described as either inelastic or elastic. Demand is said to be inelastic when a large percentage change in price brings about a relatively small percentage change in sales. For example, the demand for milk, sugar, salt and wheat may be considered as inelastic.

On the other hand, the demand is said to be more elastic when a small percentage change in price brings about a relatively large percentage in sales. The demand for automobiles, gold, wrist watches, televisions, etc. is elastic and is sensitive to price changes.

2. Cost Oriented Pricing:

Under cost pricing, the marketer primarily looks at production costs as the key factor in determining the initial price. This method offers the advantage of being easy to implement as long as costs are known. But one major disadvantage is that it does not take into consideration the target market’s demand for the product. This can present major problems if the product is operating in a highly competitive market where competitors frequently alter their prices.

There are several types of cost pricing including:

(a) Cost-Plus Pricing

(b) Markup Pricing

(c) Breakeven Pricing

Cost plus pricing is the most pervasive pricing method used by the business enterprises. Under this method, the cost estimate of the product is made and a margin for profit is added to it to determine the price. The basic philosophy behind this approach is that the sale price of a product must cover its cost and bring about a reasonable margin of profit. The margin is known as ‘mark-up’ and that is why, cost plus pricing is also known as ‘mark-up pricing’.

The simple formula used in cost plus pricing is –

Selling Price = Unit Total Cost + Desired Unit Profit

Several different concepts of cost component may be used in cost plus pricing. In general, cost means either actual, expected or standard cost. Actual cost usually means historical cost for the latest available period. It reflects recent wages and material prices and overhead charges at the current output rate. Expected cost is a forecast of actual cost for the pricing period on the basis of expected prices, output rates and efficiency.

Standard cost is a conjecture as to what cost would be at some ‘normal rate of output and with efficiency to some standard level. In practice, cost is determined on the basis of estimates and cost experience. Formulae for cost plus pricing differ widely among industries and even among firms within an industry. This variation is probably due to differences in accounting practices.

For instance, one manufacturer may start with cost of material and selling expenses and add 10% for overhead, 30% for selling expenses, and 10% for profit, and another manufacturer may add 10% of the material cost of purchasing overhead and add 125% of direct labour for general overhead. He may then add 15% of this sum for profit.

The percentage that is added for profit in cost-plus formula differs from firm to firm. The size of the mark-up depends upon competition, distinctiveness of the product, custom of the market and some vague notion of a reasonable profit. Some big organisations determine the average mark-up on cost necessary to obtain a required rate of return on their investments.

Under this policy, pricing starts with a planned rate of return on investment. To translate this rate of return into a percent mark-up on cost, it is essential to estimate a normal rate of production and its standard cost. After this, the ratio of invested capital to a year’s standard cost of normal production is computed. This is called capital turnover.

Multiplication of capital turnover by target rate of return gives the mark-up percentage to be applied to the standard cost. For instance, if capital turnover is 0.8 and the target rate of return is 15% on the invested capital, the mark-up standard cost will be 12%.

Merits of Cost-Pius Pricing:

Cost-plus or full cost pricing helps in achieving reasonable return on the amount of capital invested. It discourages the manufacturers from cut-throat competition. It is the safest method of pricing. The manufacturer will sell those products which can give him sufficient return.

Inadequacies of Cost-Plus Pricing:

Cost-plus pricing has been criticised on the following grounds:

(i) It ignores the level and nature of demand.

(ii) If fails to reflect competition in the market.

(iii) It presumes a fixed margin of profit. But in practice businessmen increase their margin of profit when they expect good demand.

(iv) The firm using cost-plus pricing never knows how much a customer is willing to pay.

(v) In practice, businessmen use rules of thumb to determine the markup on the cost of the product.

(vi) Cost-plus pricing may not always be feasible, particularly when there is idle plant capacity. In such a case, marginal costing may be useful.

This pricing policy is often used by resellers who acquire products from producers or suppliers, use a percentage increase on top of the product cost to arrive at an initial price. A general retailer may apply a set percentage for each product category (e.g., women’s clothing, household items, garden supplies, etc.) making the pricing consistent for all like-products. Alternatively, the predetermined percentage may be a number that is identified with the marketing objectives (e.g., required 20% ROI).

For retailers who purchase thousands of products, the simplicity inherent in markup pricing makes it a more attractive pricing option than other time- consuming methods. However, the advantage of ease of use is sometimes offset by the disadvantage that products may not always be optimally priced resulting in products that are priced too high or too low given the demand for the product.

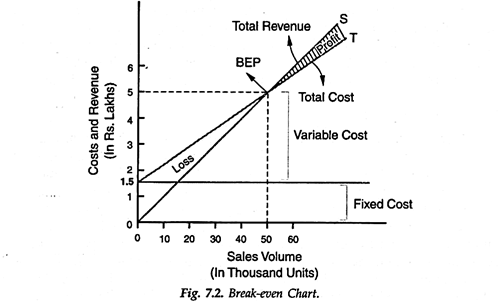

Break-even analysis uses market demand as a basis for price determination and also considers cost of production. It involves developing tables and/or charts which are useful to determine at what level of production the revenues will equal the costs assuming a certain selling price. It establishes relationship among cost of production, volume of production, profit or loss, and sale. It determines the break-even point which represents the volume of sale at which costs (fixed and variable) are fully covered.

Sales at levels above the break-even point will result in a profit on each unit. Output at any stage below the break-even point will result in a loss to the seller. Break-even analysis is a valuable pricing tool to know the expected profit or loss at various volumes of production and sales.

Break-even analysis is the most sophisticated pricing technique which takes into consideration both fixed costs and variable costs. It uses market demand as the basis of price determination.

Break-even point (BEP) which represents the volume of production at which there is no profit and loss can be calculated by the following formula:

Break-even point has been shown diagrammatically in Fig. 7.2. The vertical scale represents cost and revenue and the horizontal scale represents the sales. The fixed cost line is drawn horizontally through the fixed cost point (FC) and the total cost line is drawn from the inter-section of the fixed cost line at the left vertical scale (FT). The sales line is drawn through the zero point on the left scale (OS).

The total cost line represents the total cost of production and the sales line shows the amount of revenues (rupees in lakh) at various volumes of sales. The point at which the total revenue line and the total cost line intersect is the break-even point (BEP). The following table clearly shows cost-volume profit analysis at various levels of production.

The break-even point is 50,000 units of sale. At this point-total cost is Rs. 5 lakhs represented by Fixed Cost – Rs. 1,50,000 and Variable Cost – Rs. 3,50,000 and the total sales revenue is Rs. 5 lakhs. Thus, it is a point of no profit, no loss. The spread to the right of this point (shaded area in the figure) represents the profit potential and the spread to the left represents the loss.

Break-even analysis is not free from limitations. This techniques assumes a single product which is not possible in practice. It also assumes that all the costs can be divided into two categories only, i.e., fixed and variable, but there are certain semi-variable costs also. Therefore, it is not easy to find the marginal cost of a product. Break-even analysis is a theoretical tool to know the volume of production at which profits could be maximised.

In practice, the determination of the price is not so easy. Despite these limitations, marginal costing can prove very helpful. It can help in taking the decision whether to continue production or stop production. During depression, the management of a firm may decide to keep on market its products at the prevailing market price which is more than or equal to the variable cost because fixed costs have to be incurred whether there is any production or not.

3. Competition-Oriented or Market Driven Pricing:

The management of a firm may decide to fix the price at the competitive level in certain situations. This policy is used when the market is highly competitive and the product is not differentiated significantly, for example, Coca-cola and Pepsico fight each other everywhere in India and abroad.

This situation resembles the perfect competition under which prices are determined by the process of demand and supply. There is no product differentiation, buyers and sellers are well-informed about the market price and the market conditions, and the seller has no control over the market price. In such a situation, every firm will follow the price which is in tune with the market conditions.

Customary Pricing:

The market based pricing is also used when a prevailing or a customary price level exists. For instance, there are many soft drinks in the market which are sold to the consumers at Rupees seven only. In such a case, no producer may try to disturb the customary price.

Every manufacturer tries to adjust his cost to the customary price by reducing/ increasing the quantity of the product. If a manufacturer raises the price above the customary level, there may be a sharp drop in the demand of his products.

4. Value-Based Pricing:

Price of a product is based on what customers perceive as value. For instance, Park Avenue is considered a premium products and assigned higher value by the customers.

Under value-based pricing, price is determined by buyers’ perception of value rather than the seller’s cost. Price is considered along with other marketing- mix variables before the marketing programme is set. In traditional cost-based pricing, pricing is due after product design and setting the marketing programme. Cost-based pricing is product driven.

The company designs what it considers to be a good product, then checks the costs of making the product, and sets a price that covers costs-plus a target profit. Marketing must then convince buyers that the producer’s value at the price justifies its purchase. If the price turns out to be too high, the company must settle for lower mark-ups or lower sales, both resulting in disappointing profits.

Under value-based pricing, the company sets its target price based on customer perceptions of the product value. The targeted value and price then drive decisions about product design and what costs can be incurred. As a result, pricing begins with analysing consumer needs and value perceptions, and price is set to match consumer’s perceived value. This, it reverses the traditional process of cost-based pricing.

Many consumers perceive higher value for branded products marketed through prestigious retail outlets. In practice, there may be a little difference between two products, but consumers give high value to intangible such as brand image, packaging, seller’s prestige, etc. However, value-based pricing is difficult to measure in practice. It calls for a detailed investigation of how much the customers would pay for a basic product and for each benefit added to it.