Here is an essay on ‘Rural Marketing’ for class 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Rural Marketing’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay on Rural Marketing

Essay # 1. Introduction to Rural Marketing:

Rural marketing is generally understood as ‘marketing goods and services to villages’. Or its scope is expanded by adding the term ‘agricultural marketing’, which takes into account the flow of produce from rural to urban areas. Many articles and papers on rural marketing start by describing the huge opportunity that rural areas represent – more than 800 million people who have little access to modern goods.

Writers lament that though a large number of people live in villages, many companies have been unable to tap this big opportunity. Indeed, many writers suggest that rural marketing is an easy task- a huge opportunity to be exploited, a saviour for companies that face saturation in urban markets and a means of getting out of the recessionary cycle that urban markets are prone to.

One of the most celebrated writers, C.K. Prahalad (2005), exhorted companies to tap the fortune at the BoP, that is, to try to exploit the huge purchasing power of the large numbers of poor. His idea was to eradicate poverty through profits. Closer to home, popular literature is replete with descriptions of the wonderful opportunities offered by rural markets.

Bijapurkar and Shukla (2015) strike a similar note, “When a large mass of a whopping 180 million households starts to move, even though at varying speeds, and some quite slow, it still makes for a market opportunity that is already larger than the urban market.” Practitioners too have fallen into this trap. “The water’s warm and the ocean’s calm. Dive in; it’s time to discover what lies beyond the horizon,” is the advice given by Saigal (2015).

Based on such thinking, most writers have presented the view that rural marketing can be done by applying existing commercial marketing knowledge to a virgin market. Much of the rural marketing effort thus consists of trying to convince people in villages to buy products and brands offered by multinational companies (MNCs) and other big companies, who in turn look at population data and want to grab the unexplored potential of villages.

This is rather a simplistic understanding of the subject. Companies that have followed this proposition have faced insurmountable problems in terms of distribution of goods and selling them to consumers who have limited purchasing power and do not have access to financial markets. Many companies have discovered that marketing in rural areas is not as simple as tapping into a virgin market waiting to buy all those wonderful products that find ready buyers in urban areas.

A report by Accenture (2013) says, “India’s rural markets present opportunities that companies seeking to become high-performance businesses cannot afford to ignore. But the size and scale of those markets have been offset by concerns about the profitability of these markets and the durability of rural demand.”

Rural marketing is not simply tapping into opportunities merely by diving in. If we look closely, we find that rural marketing cannot be thought of as simply marketing in rural areas. Since even large companies struggle to get their rural marketing approach right, there is a need for a proper understanding of the subject and to redefine strategy based on market realities. We first look at the existing frameworks of rural marketing.

Essay # 2. Definition of Rural Marketing:

Based on the experience of the companies, we attempt a definition of rural marketing. The low-cost and sachet strategies that are generally quoted in this context can be easily copied and become unprofitable in the long run. These companies clearly have done something different and their guiding principles are inclusion, efficiency and innovation. These principles are illustrated in our opening case of Aravind and Narayana hospitals.

We need a definition of rural marketing that takes into account these three guiding principles if we are to succeed in rural areas. An alternative approach is therefore needed—one that sees rural consumers as people. Once we recognize that, we begin to see rural consumers as part of the developmental process and marketing acquires a deeper purpose, summed up by the definition of rural marketing provided by Pratik Modi (2009), “as any marketing activity whose net developmental impact on rural people is positive.”

Drawing from this idea, we define rural marketing as a process that consists of developing and empowering people in rural communities through capability enhancement and social innovation, to facilitate a two-way marketing of economic and social goods between rural and urban areas.

This definition can be explained as having four aspects:

1. A Process that Consists of Developing and Empowering People in Rural Communities:

Developing and empowering people means that rural incomes must be enhanced by making the people producers of economic goods. Help is provided to existing producers to become more efficient by removing market separations, and thereby enable them as consumers.

2. Two-Way Marketing of Economic and Social Goods between Rural and Urban Areas:

Any definition of rural marketing must include social goods because corporations are in a position to deliver these goods, and these are not measured in economic terms but still help in bringing large parts of disadvantaged populations within the purview of marketing.

3. Capability Enhancement:

Amartya Sen (1993) has given what is called the ‘capability approach to development’. He argues that development is about the freedom of choice in all spheres – a person’s capability refers to the alternative combinations of ‘functionings’—referring to the various things a person may value doing or being, such as being adequately nourished, being healthy and being able to take part in the life of a community. The focus of development thus morphs into increasing a person’s capability set or the freedom to lead the life she/he values.

4. Social Innovation:

Rural marketing requires a high degree of social innovation. Social innovation is defined as any new initiatives—products, services or models—that meet social needs more effectively than existing alternatives, and simultaneously create new social relationships and collaborations. INSEAD’s social innovation website defines it as “the introduction and development of new business models, and market-based mechanisms that deliver sustainable economic, environmental and social prosperity.”

New business models are created through initiative, inventiveness and creativity. This gives rise to a different type of business with primarily a social focus rather than a profit-oriented one. Such models encourage a more participatory approach. The success of Grameen Bank and Amul shows that social innovation does, indeed, create businesses that become powerful forces for the social good.

If we look at the subject from this perspective, rural marketing becomes a tool that delivers both rural empowerment and marketing of goods and services, thus broad-basing its domain to cover a variety of market relationships. This enhances the role of marketing considerably. Companies will therefore have to change their approach and their organization structures, modify their missions and invest in rural empowerment.

It may be argued that empowerment is not really a task of private companies, but unless purchasing power is enhanced, companies can only focus on a small part of the market, since many of India’s poor live in rural areas. Some companies have succeeded by linking agriculture and rural enterprises to rural and urban markets. Our mini case study on Amul shows that this has been done quite well.

This article argues for treating rural marketing as a subject, distinct from marketing, because companies should not merely sell products to rural areas but should facilitate a better standard of living for rural consumers. This can happen if companies approach the problem with two mindsets – building capabilities and investing in social innovation. This change in approach is essential if companies are to succeed in rural markets.

Since many attempts to reap the ‘fortune at the bottom of the pyramid’ have failed because they followed the traditional methods of marketing of making profits by supplying goods to the poor—a new approach is needed. Only when companies focus on the developmental aspect of their interventions, they can succeed in rural areas.

Essay # 3. Frameworks of Rural Marketing:

Ask anyone about marketing, and the answer will most probably be about selling, advertising or about some big brands. This is not surprising, because most marketing that is taught in business schools is urban market oriented. Our approach usually rests on the visible, urban aspects of marketing, and that is why we tend to ignore areas where a large number of people live. It is an approach described by the Pareto principle – that there is an unequal relationship between inputs and outputs. Urban issues get disproportionately high attention by governments, policy makers and the media, but the large section of the population that lives in rural areas is largely ignored.

That is why, most marketing undertaken in villages is seen as just an extension of urban advertising, distribution and promotion. This stream of thought tries to apply marketing principles to rural customers, based on segmentation variables and marketing finished goods to them. These companies target only those who can afford the products and is, therefore, limited in its scope. The second school of thought is that rural marketing consists of agriculture – it focuses on marketing of agricultural produce and of agricultural inputs, that is, it is limited to grains, cash crops and inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides, seeds and farm machinery.

However, selling to the poor has been unprofitable for many companies, but is also morally repugnant. Can and should the poor, whose life is a daily struggle, be seen as a source of profit?

Unfortunately, much of rural marketing literature exactly does that. It suffers from the flaw that it treats rural marketing as an extension of marketing.

Jha (1988) has shown the weaknesses of the existing rural marketing literature, which are true even today:

1. Participants – It ignores the majority of rural population, that is, the rural poor.

2. Products – It concentrates on tangibles and ignores some of the basic needs such as health, education, drinking water, housing, transportation, labour, land, money and so on. Even in tangibles, the focus seems to be exclusively on economic goods.

3. Modalities – It is not concerned about development of market centres and supporting institutions.

4. Norms – It ignores norms of behaviour, liabilities of various parties and methods of operation, even with regard to conventional goods.

5. Outcome – Marketing literature is negligent about the expected outcomes.

The companies, which change their approach to marketing and understand markets and consumers, and try to solve local problems, are more likely to be successful than mere copycats of urban strategy. But first, we learn how our understanding of rural marketing has grown over the years.

Three frameworks of rural marketing have been suggested. These are helpful to understand rural marketing but give a somewhat limited approach to the subject. The first is defining what is rural, the second is based on flow-of-goods and the third is a historical perspective.

Defining Rural:

The term ‘rural’ is defined in several ways.

According to the Planning Commission of India, a town with a maximum population of 15,000 is considered rural in nature.

The National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) defines ‘rural’ as follows:

i. An area with a population density of up to 400 per sq. km.

ii. Villages with clear surveyed boundaries but no municipal board.

iii. A minimum of 75 percent of male, working population involved in agriculture and allied activities.

The Census of India 2001 defines urban India and it is implied that rural means the areas which are not urban.

Urban India is defined as:

i. All statutory places with municipality, corporation, cantonment board or notified town area committee.

ii. Minimum population of 5,000.

iii. Density of population of at least 400 per sq. km. (1,000 per sq. mile).

iv. At least 75 percent of male, working population engaged in non-agricultural activities.

By this definition, rural means areas with population of less than 5,000. Reserve Bank of India (RBI) defines rural areas as those areas which have a population of less than 49,000 (Tier-3 to Tier-6 cities).

Private companies have their own way of defining rural markets. Their approach is on market potential – small towns that are far from big cities would also be treated as rural areas for marketing purposes. Similarly, all areas with a population of less than 5,000 are taken as rural; however, all towns with a population up to 2.5 lakh should also be included as a rural market as the marketing approach in such towns will be quite different from that of the metros.

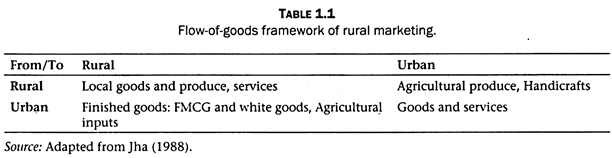

Flow-of-Goods Concept:

This concept looks at the origin of goods and their destination (Table 1.1). If goods flow from urban to rural areas, it is seen as part of rural marketing. This is the common connotation of the term. The flow of goods from rural areas to cities, and rural to rural areas, is added to rural marketing as an afterthought. In the four flows, except the flow of goods from urban to urban, the other boxes are seen to be part of rural marketing.

The kinds of goods that flow are described below:

i. Urban to Rural:

Pesticides, fertilizers, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) products, tractors, bicycles and vehicles, and consumer durables fall in this category.

ii. Rural to Urban:

In this category, we have agricultural produce such as grain, fruits and vegetables, milk and related products, forest produce, spices and so on. This is the view taken by the National Commission on Agriculture, which says that central to rural marketing is a ‘saleable farm commodity’.

iii. Rural to Rural:

This category consists of activities between two villages, such as selling tools, handicrafts, consumables and services to each other.

iv. Urban to Urban:

This category consists of goods and services produced and offered in urban areas, and these are not considered as part of rural marketing.

While this is rather broadly accepted, it raises some interesting questions:

i. Would McDonalds and other food chains be doing rural marketing because its raw materials are grown in villages, and is therefore rural to urban?

ii. Would all the fashion brands such as Arrow and Tommy Hilfiger be doing rural marketing as they make much of their apparel from cotton, which is grown in rural areas?

iii. What is the difference between the marketing done by Amul and, say, a multinational corporation?

iv. If a factory is set up in a rural area to leverage lower rentals and labour costs, would it be rural marketing?

Historical View:

Kashyap and Raut (2006) have listed three distinct phases in the evolution of rural marketing from the 1960s, during which the term changed its meaning.

These phases are described below:

i. Phase I (pre-1960) – In this phase, rural marketing was thought of as agriculture marketing, that is, of supplying rural produce to urban areas and agricultural inputs to rural markets.

ii. Phase II (1960s-1990) – In the second phase, the focus was on agricultural inputs. Marketing of non-farm rural produce was considered as rural marketing. The country had taken the road of Green Revolution, and scientific farming practices were adopted.

This led to demand of fertilizers, pesticides, high-yield variety seeds, agricultural implements such as tractors, harvesters, pump sets and so on. Companies such as Mahindra & Mahindra, Escorts, Eicher, Sriram Fertilizers and Indian Farmers Fertiliser Cooperative Limited (IFFCO) made inroads into rural areas. The government encouraged marketing of rural products and Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC) along with societies and emporiums were set up. Exhibitions and craft melas (fairs or festivals) in urban areas helped expand the market for rural products, though in limited ways.

iii. Phase III (1991-present) – In 1991, the country took steps towards liberalization resulting in focus on consumer goods. Due to saturation in cities, companies faced lack of growth in urban areas and they turned their attention to rural areas. Prahalad’s (2005) book on BoP marketing and several papers by Indian commentators gave impetus to such thought, and the recessionary periods convinced companies about the potential of rural markets and the need to exploit them.

In this viewpoint, rural marketing is understood today as the kind of marketing where multinational, large companies and retail companies go to rural areas. Rural marketing is treated as a subset of marketing, and it is assumed that existing marketing theory can be applied directly to rural areas. Keeping with this trend, Dogra and Ghuman (2008) define rural marketing as “planning and implementation of marketing function for the rural areas.” Based on such thinking, companies have tried to sell their products in villages by modifying distribution channels, or by offering smaller packs or cheaper variants.

But as Erik Simanis (2012) shows, the strategy of “low price, low margin, high volume” does not work for long. Many companies have had to withdraw from rural markets as they found them unprofitable. He writes that the model has not quite worked for a large number of companies who have ventured into rural areas.

Plenty of failures illustrate the difficulty:

i. The Indian government’s efforts at marketing a low-cost tablet computer for poor and rural students have failed miserably. The computer, called Aakash, was touted as one of the ‘world’s cheapest’ innovations. The tender was won by Datawind, which was to sell the tablets to the Indian government for about Rs. 2,290 each; the government was to subsidize, so that it would cost even less to students and teachers. The government has conceded that it was a failure.

ii. Hewlett Packard started a project called ‘e-inclusion’, which sought to enable “all the world’s people to access the social and economic opportunities of the digital age.” It had to be closed because its objectives were not tied to the company’s mission.

iii. Procter & Gamble invented a water purification powder called PUR for BoP markets, but it was a commercial failure. It is now being distributed by a philanthropic enterprise.

iv. In 2007, SC Johnson launched Community Cleaning Services, a BoP business aimed at creating employment in a slum in Nairobi, Kenya but could not make profits.

v. DuPont tried to alleviate malnutrition and open new markets by selling soya-fortified snacks in a pilot programme in India, but had to drop the project.

vi. India’s public distribution system (PDS) is a government-sponsored chain of shops for distributing basic food and non-food commodities to the needy sections of the society at very cheap prices. The system is often blamed for its inefficiency and rural-urban bias. It has not been able to fulfill the objective for which it was formed. Moreover, it has frequently been criticized for instances of corruption and black marketing, according to The Economic Times (2015).

Because of these and other failures, many people have questioned whether there is a mirage at the BoP. But The Guardian (2014) notes, “That doesn’t mean that business should leave the task of fighting poverty to governments or aid organizations. Companies can bring unique value to the poor.”

The mistake made by these initiatives is that only one aspect of the marketing mix was sought to be changed—packaging, pricing or distribution. Rural marketing, however, calls for a paradigm shift in approach.

Applying existing marketing theory to rural marketing does not quite work because many questions arise when we see market realities, some of which are as follows:

1. Distribution – How to send small packets over large distances where transportation or courier services are irregular or non-existent?

2. Promotion – How to promote goods in areas which are media dark, lacking regular communication channels?

3. Pricing – How to keep prices low when the costs of sending goods and servicing them in remote areas are extremely high?

4. Feudal Outlook – How to promote modern products in areas which see modernization as a threat to their culture?

5. People – How to find educated managers willing to work in rural areas, where sending sales or service personnel regularly is uneconomical?

6. Payments – How to collect payments, sometimes very small, from areas where intermediaries are poor and lack access to formal financial channels?

7. Intermediaries – How to find warehouses and intermediaries to support the marketing activities of companies?

8. Purchasing Power – How to sell in areas where people are desperately poor and farmers are committing suicide because of economic reasons?

9. Sachet Marketing – How to achieve volumes and a high penetration rate to make low-priced sachet marketing profitable?

10. Selling Effort – How to deploy, train and retain the sales force in geographically diverse areas?

These questions are enough to flummox the brightest marketing students and managers, but must be asked before a company embarks on a rural marketing adventure. They also show why existing marketing knowledge cannot be applied to rural areas, and why a new approach in rural marketing is needed.

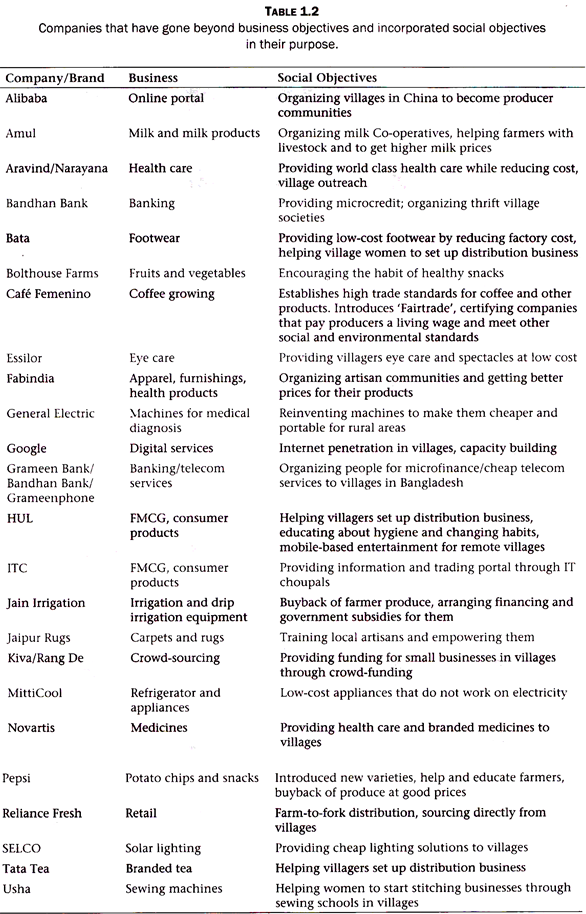

This new approach consists of social innovation, or applying new ideas that work in meeting social goals. Several companies are describing that have adopted unique and innovative approaches in rural areas. We see from the experience of these companies (Table 1.2) that mere selling of goods in rural areas is not enough, but companies have to rise to solve some local problems so as to be accepted in rural society.

As Anderson and Markides (2007) explain, it is not about creating new product features but adapting existing products to customers who have fewer resources or a different cultural background. It is less about creating new business models or competing, but about establishing basic market ingredients such as distribution channels and customer demand from the ground up.

Essay # 4. 5D Framework of Rural Marketing:

The 5D framework proposed by Bhan (2009) gives another aspect to rural marketing and stresses on the need for design, distribution, demand, development and dignity.

It looks at products from the point of view of customers—that all products or services must have an immediate value for BoP consumers. Through design, they should provide value to rural consumers, distribution should ensure easy availability, demand has to be created and then matched by supply, development improves the purchasing power of consumers and dignity means not talking down to consumers. The basis of this approach is that those in the lower income strata, particularly in the developing world, are not really ‘consumers’ but extremely careful ‘money managers’ who must allocate resources for betterment of their families. Expenses are often seen as investments that give the best returns.

Products meant for rural areas must satisfy some unmet needs and also enhance the livelihood or quality of life of rural consumers. All products have to, therefore, focus on benefits and keep into account the ground realities in which the product will be bought and consumed.

The 5D elements are explained below:

1. Design:

Products must be designed specifically for rural areas. Merely offering cheaper versions by lowering quality would be a bad strategy. Instead, companies have to invest in ‘reverse engineering’, which means starting with the price the customer can pay, then innovating to deliver products and thereby make a profit. That is why design plays an important role and offerings must be redesigned to meet customer needs. There are many examples of such redesign efforts that have delivered value to rural customers and profits to companies.

Low-cost refrigerators that work on limited or no electricity supply, reusable packaging, solar charging batteries that power small lighting sources, portable medical devices and so on have been designed to meet marketing realities in rural areas. Companies often make the mistake of treating rural customers like those in the west who have to be attracted to products in the face of almost unlimited choices, but in rural markets the customer has very limited choices and must perceive value in the product.

2. Distribution:

There is a need to strike alliances among companies to reach remote areas. Since traditional channels do not work, innovative distribution methods are used in rural areas. Distribution in rural areas must be lean and incur low cost. Channels must acquire the ability to cater to small demand from scattered areas and somehow reach goods where they are needed in time.

3. Demand:

Several challenges arise in managing demand. First is to communicate with customers so that they get interested in products, second is supplying small quantities on a regular basis and third is keeping in constant touch with consumers to assess future demand. In cities, wholesalers aggregate demand and place orders in economic quantities, but in rural areas retailers are small and demand is difficult to assess.

4. Development:

Companies have to invest in the social and economic development of communities they wish to serve commercially in order to raise the incomes of the people living in them. Initiatives to increase employment or to improve education and health will have impact on their earning power, thereby increasing the market size. It may be argued that development cannot be done by private companies and is in the purview of government agencies. But unless people get more incomes, they will hardly be able to buy the products, no matter how good they are. Collaborations with other companies, investments in technology and working with NGOs are ways of developing and serving rural markets.

5. Dignity:

This is an important addition to the rural marketing framework that is ignored by other models. Companies often start selling lower quality goods in rural areas, which labels the consumer in a way that is demeaning to them. Rural consumers do not want to be talked down to nor do they want to see themselves as being deprived. That makes rural marketing quite complex. Marketing managers trained in traditional marketing practices will have to change their mindset and develop new sets of tools keeping in mind the dignity of consumers.

Essay # 5. Process of Rural Marketing:

The rural marketing process must remove all the separations. Based on these, we describe the rural marketing process as consisting of five tasks.

The five steps are described below:

1. Product Redesign:

Products have to be redesigned to deliver value. It calls for innovation in both design and pricing, reducing costs across production and distribution. The customer should be able to see the value in buying the product, that is, it must make life of the rural customer simpler in some way.

2. Awareness:

Companies have to develop capabilities for BTL campaigns, arranging demonstrations and encouraging trials. They must also identify opinion leaders and have a system of approaching such individuals regularly with information on new products and to maintain relationships. For example, the Kan Khajura Tesan (KKT) initiative of HUL, which offers ad-based entertainment on demand, is a channel created specifically for rural areas.

3. Purchase:

The product offered for purchase has to be backed by supply and payment chains. These too have to be reinvented for rural areas. Supply chains must overcome the lack of transport channels and that too with regularity, while payments channels have to account for a large number of small transactions. Purchase is facilitated when both these systems are in place.

4. After-Sales Service:

Innovative approaches are needed to create after-sales service in rural areas. Companies have to invest in mobile units or other means to establish a presence in areas where footfalls are low, such as Honda.

5. Word-of-Mouth Recommendations:

A good purchase experience followed by good service establishes positive word-of-mouth publicity for the company. When community leaders are also involved, this translates into wide publicity.

Essay # 6. Barriers and Enablers of Rural Marketing:

For success in rural areas, companies have to understand both the barriers and enablers to marketing, which are described below:

Facilitating the Process:

The reason that companies face problems in realizing the rural marketing potential is that they fail to address the problem of inadequate infrastructure, low literacy and high levels of poverty. That is why, projections of topline growth and market penetration in rural areas often go haywire and the sustainability of the rural marketing initiatives comes into question. Lack of connectivity, bad roads, railways and communication channels are big hindrances.

Other problems are lack of skilled talent, fragmented demand patterns, the lack of information on rural markets and consumers, and limited access to financing options. Timely data collection on demographics and consumption patterns is difficult; data analysis is not easier. As rural customers depend on agriculture, poor crops can reduce demand projections. The rural marketing process is facilitated by removing the barriers and supporting the enablers (Table 1.5).

In its study, Accenture (2013) found that rural markets account for a significant portion of revenues and profits for many companies that have been able to use the enablers and got over the barriers in rural marketing.

What these companies have done is summarized here:

1. Reach ‘the Last Mile’:

To reach the last mile, companies depend on either traditional channels or small traders. Small traders visit towns using small vehicles such as tempos, scooters and bicycles. They buy stocks in small quantities to sell in villages. This system is irregular and is limited by the reach of the small trader. In traditional channels, the sub-dealers or sub-stockists buy from wholesalers and serve small towns and large villages. Remote villages remain unserved as it is not economical to send small quantities of goods.

To reach the last mile or small villages, some companies have used the concept of village entrepreneur—individuals who sell products in their villages on a part-time basis. This ‘feet-on-street’ approach can help in reaching villages where sub-stockists cannot reach, but the company has to change its own marketing set-up to deal with thousands of such village entrepreneurs. Others methods tried by companies are to add levels to their distribution channels or by using e-commerce to reach interiors.

2. Micro-Segmentation:

Companies use micro-segmentation techniques to locate small segments of population that are doing better than others. By targeting these prosperous customers rather than the rural market as a whole, they are able to build sizeable volumes. Technologies, such as GIS mapping help to locate such segments.

3. Channel Relationships:

Another essential is that companies must build skills of channel partners and village entrepreneurs. Most operate on the small scale. Upgrading them on skills and even financial assistance to achieve scale is required. Further, companies have to build partner relationships to achieve passion and motivation. Even familial bonds have to be built with partners. Amul, for instance, went the extra mile and developed bonds with its suppliers through services for their animals.

4. Value Propositions:

Many companies make the mistake of targeting rural markets without trying to understand the cultural, economic and demographic factors. But since rural consumers are not a homogeneous market, value propositions created for urban markets do not work. Creating customer value propositions in rural marketing consists of first understanding customers, their needs and how the brand fits in their lives. Since traditions and societal bonds are strong, companies also have to understand how these influence purchase decisions. These propositions must then be communicated in the local idiom.

5. Involve Stakeholders:

To gain inroads into village societies, all stakeholders have to be involved. Companies have to prove that the business is beneficial for everyone. By focusing on consumers’ needs rather than on profits, companies build symbiotic relationships with stakeholders, creating an ecosystem to build awareness of their brands. By integrating local populations into their value chains and creating a vested interest in the company’s survival, companies align their long-term interests with development of local communities.

6. Engage Influencers:

More than media, word-of-mouth communication plays a very significant role in rural marketing. Companies have to identify these influencers and recruit them for spreading awareness about their products and brands.

7. Rural Customer Retention:

Customers can be retained by providing reliable and consistent after-sales service. Since building service centres in distant villages is not economically feasible, low-cost service models have to be created. Developing local resources and building low-cost support infrastructure can reduce the costs of delivering service in villages.

For example, Honda has developed mobile service vans that take the dealership and service right to the doorstep of the rural customer, at a very effective cost. Such initiatives help in customer retention and generate crucial market intelligence. It also strengthens rural bonds and relationships, which increases customer loyalty and builds trust.

8. Rural Investments:

Rural markets are expensive to enter, especially when companies are bound to build infrastructure. These investments yield slow returns. For example, one information kiosk containing a computer with a V-SAT connection, costs between Rs. 2-4 lakhs and additional expenses for maintenance. A company that wishes to provide information services in villages must be prepared to invest crores of rupees in building infrastructure and revenues will be slow to come. Cash flow will consist of indirect revenue streams that are difficult to attribute to infrastructure. The payback period of such schemes is quite long – can companies afford to make such investments?

9. Skilled Local Talent:

Another problem faced by companies is to find skilled people. City-bred managers do not want to work in rural areas and local talent is not available. Young people too are not willing to stay in villages.

10. Flexible Approaches:

Large companies are unable to create flexible business models because their organizational structures are rigid. This becomes a key internal barrier to establishing a successful rural presence.

Essay # 7. 4A Approach to Rural Marketing:

Marketing students are quick to learn the concept of marketing mix consisting of the 4Ps. While the 4P framework provides a basis of understanding the subject, it needs modification to work in rural markets. The 4A approach modifies the 4P approach and helps change the focus of companies marketing in rural areas, with acceptability, affordability, availability and awareness as its focus.

The traditional approach of offering suitable products, building distribution chains, adjusting the price-value equation and using effective promotion must necessarily be modified because rural consumers are unlike urban ones. “By focusing managerial attention on creating awareness, access, affordability and availability (4As), managers can create an exciting environment for innovation,” writes C.K. Prahalad (2012).

The suggested 4A framework consisting of availability, affordability, acceptability and awareness modifies the 4P framework.

The approach is described below:

i. Product—Acceptability:

Rather than focusing on product features, companies have to modify the products to gain acceptability in rural areas. This means understanding customers and modifying products to suit their needs. It also means incorporating features that make the products more useful in rural areas. For instance, in rural areas that suffer erratic electric supply, mobile phones have been made more useful by adding the torch feature. Companies providing phones with local language displays are more popular than the ones with English displays only. This is how products are made acceptable to rural consumers.

Government data shows that much of rural population has low incomes and seasonal jobs related to agriculture. This means that companies have to cater to millions of people who are poor and have low disposable incomes. Affordability of the product or service thus becomes of prime importance. Some companies have addressed this problem by introducing small packs and sachets. They have helped companies penetrate rural markets. Such packs make a variety of products more affordable, encouraging trials and use.

Most FMCG companies have followed this strategy to enter rural markets through small packs of soaps, shampoos, beverages, biscuits and butter to boost consumption and make products affordable. However, distribution and profitability of small packs remains in question. Companies must sell small lots of five or ten sachets to small shopkeepers who are scattered over large areas. Such shopkeepers also require regular servicing. But employing a large number of salespersons results in the operation becoming unprofitable, because volumes are difficult to build and penetration rates remain low.

Other companies have developed cheaper variants of their products. This sometimes does not quite work because consumers in rural areas are value conscious. Cheap products are in any case supplied by local manufacturers, so brands have to think of innovative strategies.

ii. Price—Affordability:

One common mistake is to assume that rural areas will buy cheap products since many people living there are poor. But one of the important keys to rural markets is affordability, that is, the ability of customers to pay for products that provide reciprocal value. Further, rural consumers do not want bells and whistles with their products, but ones that are functional and sturdy that work in the rural environment. Hence, pricing of product offerings with respect to value becomes crucial. Since affordability does not mean selling cheap and low quality products, companies have to take innovative approaches to meet customers’ expectations within their ability to pay.

Assuming that the product is made available, companies have to make their products acceptable to rural people. Products that are designed specifically for rural markets—fulfilling a felt need or delivering value—stand a better chance of getting accepted. This means that companies must understand the rural consumers and think creatively to solve their problems.

iii. Place—Availability:

Since villages are scattered over large distances, companies have to focus on availability by building distribution channels that are able to fulfill small orders on a regular basis. The task is not easy, as rural roads and transportations are not dependable. Companies are thus unable to build regular supply channels. Many depend on their dealers who send goods only when it is economically viable for them. This results in irregular supply. But building supply channels for India’s more than 6 lakh villages spread over 3.2 million sq. km is more than a logistical task.

Product availability and visibility affects purchase decision and brand choice, volumes and market share. But distributors do not find it economically feasible to send stocks, and collecting payments is not an easy task. Companies have traditionally relied on distributors, hiring sub-dealers or travelling traders. These traders visit the nearby town, load their vans with an assortment of goods and sell in villages. Making use of sub-stockiest or sub-dealers in rural India has been found to be successful for many product categories but deep penetration cannot be achieved.

Other companies have adopted direct selling, using company delivery vans, tying up with noncompeting companies or setting up stalls in rural melas or haats (markets, held on a regular basis in rural areas). A variety of vehicles, including autorickshaws, bullock carts and even boats in the backwaters of Kerala are used. Rural markets or mandis (wholesale agricultural markets) are used for direct sales by many companies. Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited initiated a ‘Rural Marketing Vehicle’ designed for the supply of cooking gas to villages.

Some large companies have got over the problem of availability by creating a whole ecosystem from the scratch and tried to remove market separations. By helping rural people, they created supply chains as well as fulfilled their social responsibility. Schemes, as ITC’s e-choupal have provided rural infrastructure and resulted in creating supply chains to rural areas.

iv. Promotion—Awareness:

There are three main problems in rural promotions. First, these have to focus on creating awareness in the local idiom. Second, since the reach of the mass media is limited in rural areas, companies have to depend on below-the-line (BTL) techniques, which are difficult and costly to organize over a very large number of villages. Third, the communication has to be region specific, so the messages have to be changed for every micro-market. Companies that are tuned to using mass media through uniform national campaigns, thus have to change their entire approach towards creating awareness.

Much of the focus on spreading awareness is on the ‘communication mix’ that works in urban markets. In rural areas, the need is to start social movements that can accelerate diffusion of products and ideas across the population. How Dr. Muhammad Yunus spread the idea of microcredit, but, as Kumar (2015) writes, “If a movement is seen as a quick marketing fix, it is highly unlikely to succeed.”

Though television penetration has increased, availability of electricity remains a problem. That is why, BTL campaigns using targeted, unconventional media must be used. Events, such as fairs and festivals are occasions for brand communication, since outings are rare and those are means of enjoyment and splurging.

Local fairs and festivals thus hold a special place in rural marketing. Cinema vans, shop-fronts, walls are other means that have been utilized to increase brand visibility. Using traditional arts is also very effective in its awareness campaigns in rural areas. The key dilemma for companies is to reach rural areas without hurting the company’s profit margins.

Essay # 8. Ethical Issues in Rural Marketing:

Several ways of reaching rural market carries an inherent danger – do we not risk endangering the rural way of life and rural livelihoods? Insofar as removing rural poverty is concerned, there can be no quarrel, but marketing managers must face an ethical question while selling modern goods in rural areas – should they make money from the poor?

Students of rural marketing will do well to ponder over ethical questions such as:

1. Do we have the right to introduce an economic system of consumption and show off to villages? Should we introduce waste and pollution in villages, which are necessary byproducts of marketing?

2. Should we, by selling our wonderful products in villages, destroy rural cultures and traditional ways of life?

3. Is our urban thinking and economic system better than traditional knowledge?

4. Should we start marketing to villages simply because we do not see growth in urban markets?

5. Is it right to pretend to solve rural problems such as hygiene and health when we are, in fact, merely pushing our products in the guise of social causes?

6. Should companies profit from rural people, most of them being poor and destitute?

There are no easy answers to these questions. It cannot be denied, for instance, that the penetration of the modern economic system into traditional societies has proved to be disastrous to local people and their traditional livelihoods. The free market model of capitalism that dominates our approach has caused economic and social marginalization of local communities and has resulted in enormous misery for them, and they have been excluded from the development process. Indigenous people have been forced out of their ancestral lands to make way for dams and factories, while they have been left to deal with the consequences of loss of land and livelihood.

What Schumacher wrote in 1973 about the rural poor is sadly true even today:

Their work opportunities are so restricted that they cannot work their way out of misery. They are underemployed or totally unemployed, and when they do find occasional work their productivity is exceedingly low. Some of them have land, but often too little. Many have no land and no prospect of ever getting any. They… then drift into the big cities. But there is no work for them in the big cities either and, of course, no housing. All the same, they flock into the cities because the chances of finding some work appear to be greater there than in the villages where they are nil.

Modern development results in a systematic depreciation of village people and the sheer neglect of small towns and villages in India is a testimony of this thinking. While in marketing we must necessarily talk of selling products to and from villages, students of rural marketing must keep the ethical questions firmly in their minds. When we do this, we find that the scope of the subject increases tremendously. The approach is to highlight those initiatives that enhance lives in rural areas but not at the cost of bulldozing them. The emphasis is on inclusion, efficiency and innovation rather than imposing urban ideas on rural people.

The approach of rural marketing, therefore, must be in line with the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) – increases livelihood assets and their access, empower people and increase opportunities for diversification of livelihoods.

The companies that focus on these objectives and keep social objectives as contributing to commercial objectives, rather than the other way round, have a better chance to succeed in rural markets. As McElhaney (2008) writes, companies have to fully integrate social objectives into the governance of the company and into existing management systems. Fortunately, there are a large number of companies that are doing this.